Blog

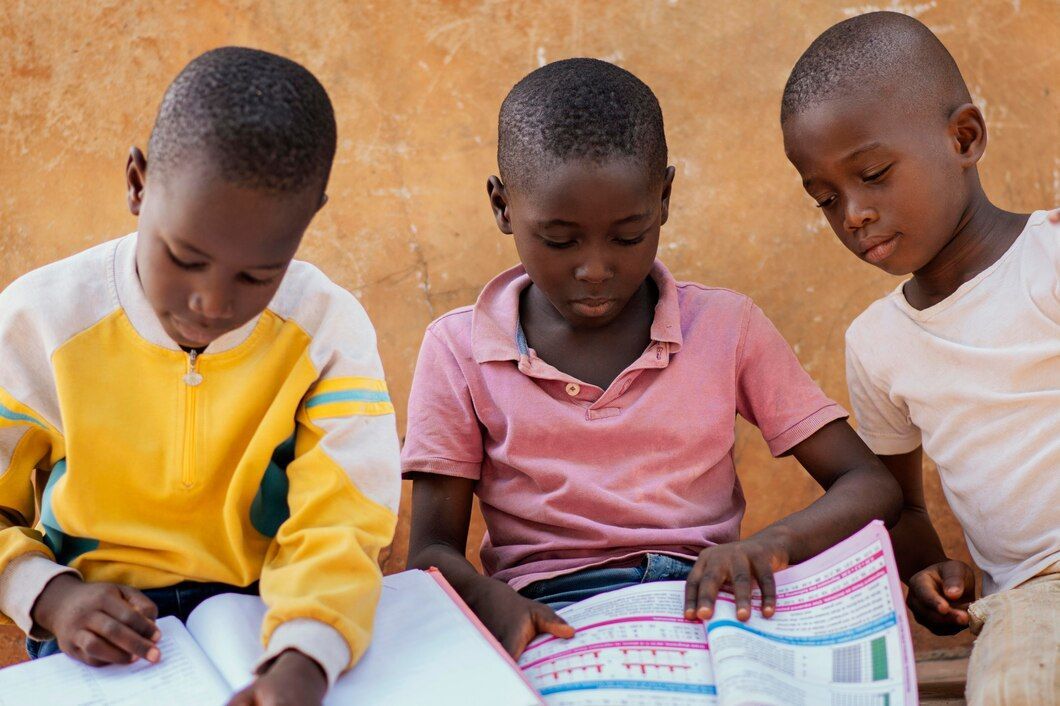

Illiteracy and poverty have long been intertwined, with each factor exacerbating the other in a vicious cycle. An estimated 774 million adults worldwide lack basic literacy skills, with the vast majority living in developing regions like Sub-Saharan Africa and South Asia. While the global rate of extreme poverty has declined in recent decades, the poorest countries continue to have the highest rates of illiteracy. It is no coincidence that the least literate populations are also the most impoverished. Illiteracy impacts an individual’s ability to earn income and attain economic security. Those without basic reading, writing, and numeracy skills face limited job prospects and lower earning potential. On average, illiterate adults earn 30-42% less than their literate counterparts. Their opportunities for stable employment and career advancement are severely constrained. Unemployment and poverty are therefore inextricably linked to illiteracy. For women in patriarchal societies, illiteracy acutely restricts economic empowerment. Female literacy rates lag significantly behind men’s in many developing nations. Uneducated girls grow up to face marginalization in the labor force. Even basic tasks like managing household finances become challenging without literacy. This entrenches gender inequality and deepens the feminization of poverty. At a macro level, widespread illiteracy undermines a country’s economic growth and perpetuates poverty cycles. Human capital development hinges on education. An unskilled, poorly educated workforce hinders productivity and innovation. This, in turn, deters domestic and foreign investment in the economy. The result is stagnation, fewer jobs, lower incomes, and greater poverty. For instance, the adult literacy rate of Mali stands at just 35% and it remains one of the poorest countries in the world. Illiteracy also has intergenerational effects that can lock families into chronic poverty across decades. Children of illiterate parents are less likely to receive an education themselves. This limits their prospects and hampers social mobility. Impoverished parents may require children to work rather than attend school, thereby propagating illiteracy across generations. Families can remain trapped in poverty for generations due to this cycle. At the same time, poverty begets illiteracy in an intergenerational cycle. Extremely poor families cannot afford the costs of schooling like uniforms, textbooks, and fees. Children may have to walk miles to the nearest school or work to support their families. The deprivations of poverty foster school drop-outs and low educational attainment. This, in turn, restricts earning ability and makes escape from poverty even more unlikely. Tackling illiteracy is therefore imperative to reducing poverty worldwide. Global initiatives like Education for All aim to achieve universal primary education in all countries. NGOs run literacy programs targeting disadvantaged groups like girls, rural populations, and ethnic minorities. Developing nations are expanding school access and retention for impoverished communities. But much work remains to dismantle the deeply entrenched barriers of poverty, gender bias, and lack of resources that fuel illiteracy. The world will make little headway on ending extreme poverty unless equal priority is accorded to ending illiteracy. Education is the key that unlocks human potential and opens doors to economic security. Investments in universal quality education and adult literacy programs can equip people with the tools to lift themselves out of poverty. Educating girls, in particular, has cascading positive effects on family welfare and prosperity. By breaking the intergenerational cycle of illiteracy and poverty, the world’s poor can aspire to a brighter future.

The ability to read and write is a fundamental life skill that many take for granted. However, for a significant portion of the population, illiteracy remains a major barrier to advancement and participation in society. Research has consistently shown high rates of illiteracy among prison inmates, suggesting a strong connection between lacking literacy skills and involvement in the criminal justice system. Recent statistics indicate that as much as 75% of state prison inmates did not complete high school or earn a GED, which implies low literacy and reading comprehension abilities. Additionally, studies of federal and state prisons have found inmate literacy rates ranging from 50-75% reading below a 6th grade level. With such a large percentage of prisoners exhibiting very low literacy, there appears to be a clear correlation between poor reading/writing skills and incarceration. There are several explanations for why individuals with limited literacy often end up incarcerated. Those who struggle with reading and writing face disadvantages in academics starting at a young age. They are more likely to fall behind in school, fail to comprehend materials, and drop out before earning a high school diploma. This lack of education can severely limit employment opportunities and put individuals at higher risk of poverty. Financial instability and inability to find legal work due to illiteracy increase the likelihood that individuals turn to illegal activities to earn income. Furthermore, lower literacy makes it difficult to navigate important documents like leases, bills, contracts, and court papers. Legal misunderstandings and vulnerabilities may then land functionally illiterate people in jail. Once incarcerated, deficiencies in reading and writing make rehabilitation and skills training programs much harder for inmates to comprehend and complete. Their chances of returning to prison skyrocket due to an inability to improve work qualifications or learn to function within the law. Thus, illiteracy and incarceration feed into each other in a problematic loop. Society clearly needs to prioritize education and literacy development to help stop this cycle. More reading assistance and adult education programs could identify those struggling with serious reading deficits before they end up in prison. Private sector partnerships withcorrectional facilities could also expand remedial reading courses for inmates. Additionally, policy changes like later school start times, improved early literacy curriculums, and mentorship initiatives focused on disadvantaged youth could help reduce high school dropout and improve literacy over the long term. If we want to address mass incarceration, reducing illiteracy must be part of the solution. The ability to read and comprehend the written word unlocks human potential and is essential for navigating modern life. Making literacy instruction and support widely available needs to become a top priority if we hope to lower incarceration rates and open more opportunities to all. Tackling illiteracy is challenging but necessary work to create a more just and equitable society.